“I’m spiritual but not religious.” You’ve heard it—maybe even said it—before. But what does it actually mean? Can you be one without the other? Once synonymous, “religious” and “spiritual” have now come to describe seemingly distinct (but sometimes overlapping) domains of human activity. The twin cultural trends of deinstitutionalization and individualism have, for many, moved spiritual practice away from the public rituals of institutional Christianity to the private experience of God within. In this conclusion of a two-part series on faith outside the church (read the first part, on those who “love Jesus but not the church”), Barna takes a close look at the segment of the American population who are “spiritual but not religious.” Who are they? What do they believe? How do they live out their spirituality daily?

Two Types of Irreligious Spirituality

To get at a sense of spirituality outside the context of institutional religion, Barna created two key groups that fit the “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) description. The first group (SBNR #1) are those who consider themselves “spiritual,” but say their religious faith is not very important in their life. Though some may self-identify as members of a religious faith (22% Christian, 15% Catholic, 2% Jewish, 2% Buddhist, 1% other faith), they are in many ways irreligious—particularly when we take a closer look at their religious practices. For instance, 93 percent haven’t been to a religious service in the past six months. This definition accounts for the unreliability of affiliation as a measure of religiosity.

A sizable majority of the SBNR #1 group do not identify with a religious faith at all (6% are atheist, 20% agnostic and 33% unaffiliated). In order to get a better sense of whether or not a faith affiliation (even if one is irreligious) might affect people’s views and practices, we created a second group of “spiritual but not religious,” which focuses only on those who do not claim any faith at all (SBNR #2). This group still says they are “spiritual,” but they identify as either atheist (12%), agnostic (30%) or unaffiliated (58%). For perspective, of all those who claim “no faith,” around one-third say they are “spiritual” (34%). This is a stricter definition of the “spiritual but not religious,” but as we’ll see, both groups share key qualities and reflect similar trends despite representing two different kinds of American adults—one more religiously literate than the other. In other words, it does not seem as if identifying with a religion affects the practices and beliefs of these groups. Even if you still affiliate with a religion, if you have discarded it as a central tenet of your life, it seems to hold little sway over your spiritual practices.

These two groups differ from the “love Jesus but not the church” crowd in significant ways. Those who Barna defined as loving Jesus but not the church still strongly identify with their faith (they say their religious faith is “very important in my life today”), they just don’t attend church. This group still holds very orthodox Christian views of God and maintains many of the Christian practices (albeit individual ones over corporate ones). As we’ll see below, though, the “spiritual but not religious” hold much looser ideas about God, spiritual practices and religion.

The spiritual but not religious hold much looser ideas about God, spiritual practices and religion.

Demographic Trends: Southwestern and Liberal

These two groups equally make up around 8 percent of the population (combined, they make up 11 percent of the population—as there is some overlap between the two). In terms of demographics, there aren’t a lot of surprises here. The groups include more women than men—who generally identify more with religion and spirituality than men—and are concentrated in the West Coast and the South. The former a likely result of the influence of Eastern religions and the latter a result of general religious inclinations. They are mostly Boomers and Gen-Xers, though the first group is slightly older and because fewer young people tend to affiliate with a religion, the second group is slightly younger.

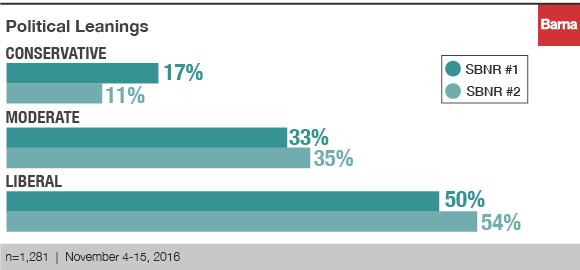

But their political leanings are where it gets interesting: Both groups identify as liberal (50% and 54%) or moderate (33% or 35%), with only a fraction identifying as conservative (17% and 11%). Yes, conservatism and religiosity tend to go hand-in-hand, but this divide is unusually stark. It may be that left-leaning spiritual seekers feel they are without a spiritual home in the church, a place they likely view as hostile to their political attitudes, particularly around hot button—and often divisive—issues like abortion and same-sex marriage.

Redefining “God”

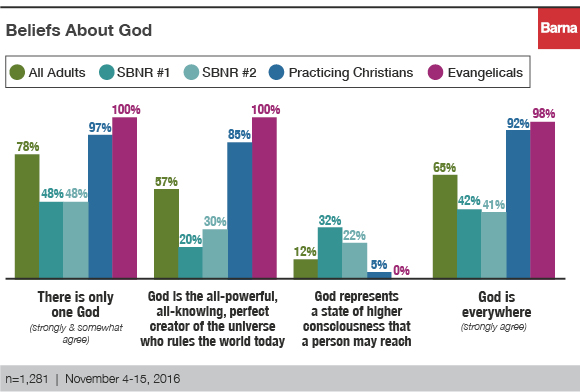

As one might expect—and in stark contrast to the “love Jesus but not the church” crowd—both groups of “spiritual but not religious” hold unorthodox views about God or diverge from traditional viewpoints. For instance, they are just as likely to believe that God represents a state of higher consciousness that a person may reach (32% and 22%) than an all-powerful, all-knowing, perfect creator of the universe who rules the world today (20% and 30%). For context, only one in 10 (12%) American adults believe the former, and almost six out of 10 (57%) believe the latter. So these views are certainly out of the norm. The trend continues: They are just as likely to be polytheistic (51% and 52%) as monotheistic (both groups: 48% each), and significantly fewer agree that God is everywhere (41% and 42%) compared to either practicing Christians (92%) or evangelicals (98%). But straying from orthodoxy is not the story here. This feels expected. Sure, their God is more abstract than embodied, more likely to occupy minds than the heavens and the earth. But what’s noteworthy is that what counts as “God” for the spiritual but not religious is contested among them, and that’s probably just the way they like it. Valuing the freedom to define their own spirituality is what characterizes this segment.

Ambivalent Views of Religion

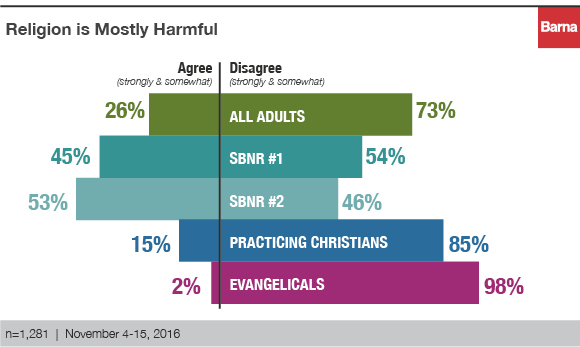

By definition, the “spiritual but not religious” are religiously disinclined, and the data bears this out in a number of ways. Firstly, both groups are somewhat torn about the value of religion in general, holding ambivalent views (54% and 46% disagree, and 45% and 53% agree), especially compared to religious groups (i.e. practicing Christians: 85% disagree and evangelicals: 98% disagree). So why the ambivalence? It’s one thing to be disinclined, but it’s another to claim harm. The broader cultural resistance to institutions is a response to the view that they are oppressive, particularly in their attempts to define reality. Seeking autonomy from this kind of religious authority seems to be the central task of the “spiritual but not religious” and very likely the reason for their religious suspicion.

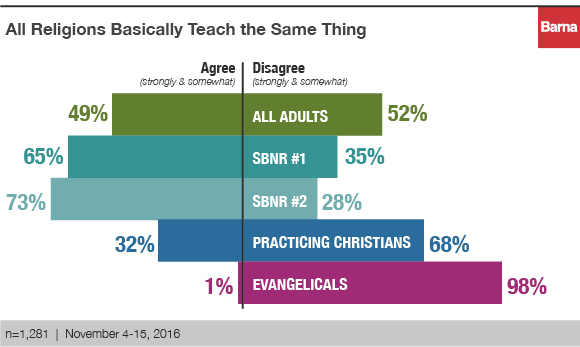

Secondly, as functional outsiders, their view of religious distinctiveness is much looser than their religious counterparts. A majority of both groups (65% and 73%) are convinced that all religions basically teach the same thing, particularly striking numbers compared to evangelicals (1%) and practicing Christians (32%). Again, the “spiritual but not religious” shirk definition. The boundary markers are non-existent, and that’s the point. For them, there is truth in all religions, and they refuse to believe any single religion has a monopoly on ultimate reality.

Spirituality That Looks Within

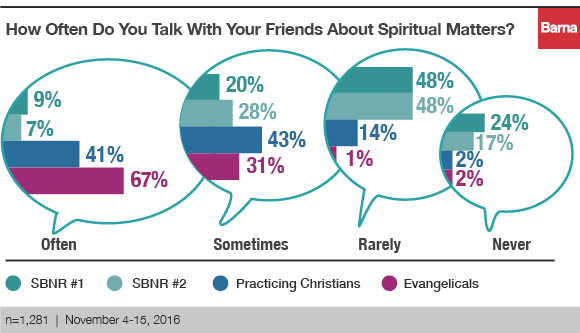

As we’ve seen, to be religious is to be institutional—it is to practice one’s spirituality in accordance with an external authority. But to be spiritual but not religious is to possess a deeply personal and private spirituality. Religions point outside oneself to a higher power for wisdom and guidance, while a spirituality divorced from religion looks within. Only a fraction of the two spiritual but not religious groups (9% and 7%) talk often with their friends about spiritual matters. Almost half (48% each) say they rarely do it, and they are 12 (24%) to eight (17%) times more likely to never talk with their friends about spiritual matters than both practicing Christians and evangelicals (2% each).

Spiritually Nourished on Their Own—and Outdoors

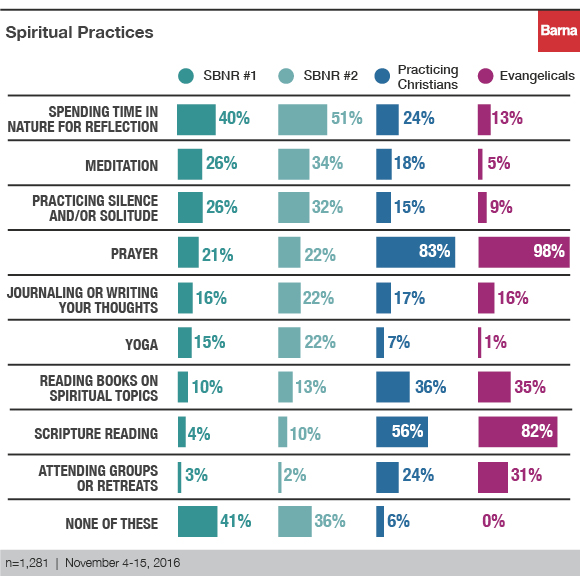

Like the “I love Jesus but not the church” group, the “spiritual but not religious” live out their spirituality in the absence of the institutional church. But they still take part in a set of spiritual practices, albeit a mish-mash of them. Somewhat unsurprisingly, they are very unlikely to take part in the most religious practices like scripture reading (4% and 10%), prayer (21% and 22%) and even groups or retreats (3% and 2%), particularly compared to the other religious groups. Their spiritual nourishment is found in more informal practices like yoga (15% and 22%), meditation (26% and 34%) and silence and / or solitude (26% and 32%). But their most common spiritual practice is spending time in nature for reflection (40% and 51%). And why not, considering the real sense of personal autonomy gained from time outside. Overall, it’s easy to see why this group, who make sense of their lives and the world outside religious categories, are inclined toward more informal and more individual modes of spiritual practice.

What the Research Means

“In the recent study on those who ‘love Jesus but not the church’, we explored what religious faith outside of institutional religion looks like. In this study, we are exploring what spirituality outside of religious faith looks like,” points out Roxanne Stone, editor in chief at Barna Group. “While this may seem like semantics or technical jargon, we found key differences between these groups. The first is disenchanted with the church; the second is disenchanted with religion. The former still hold tightly to Christian belief, they just do not find value in the church as a component of that belief. The latter have primarily rejected religion and prefer instead to define their own boundaries for spirituality—often mixing beliefs and practices from a variety of religions and traditions.

“They represent an equal percentage of the population,” says Stone. “And, by all indications, both groups are growing. Those who love Jesus but not the church are certainly more favorable toward religion and would likely be more receptive to re-joining the church. Yet, spiritual leaders should not discount this group of the ‘spiritual but not religious.’ They are distinct among their irreligious peers in their spiritual curiosity and openness. The majority of those who have rejected religious faith do not describe themselves as spiritual (65%), similarly two-thirds of those with no faith at all do not identify as spiritual. So those who do—this group of the spiritual but not religious—display an uncommon inclination to think beyond the material and to experience the transcendent. Such a desire can open the door to deep, spiritual conversations and, in time, perhaps a willingness to hear about Christian spirituality. The bent of those conversations necessarily must be different though than with those who love Jesus but not the church. The wounds and suspicions toward church will come from different places—as will their understanding of spirituality. But both groups represent people outside of church who have an internal leaning toward the spiritual side of life.”

They are distinct among their irreligious peers in their spiritual curiosity and openness.

Comment on this research and follow our work:

Twitter: @davidkinnaman | @roxyleestone | @barnagroup

Facebook: Barna Group

About the Research

Interviews with U.S. adults included 1281 web-based surveys conducted among a representative sample of adults over the age of 18 in each of the 50 United States. The survey was conducted in April and November of 2016. The sampling error for this study is plus or minus 3 percentage points, at the 95% confidence level. Minimal statistical weighting was used to calibrate the sample to known population percentages in relation to demographic variables.

Millennials: Born between 1984 and 2002

Gen-Xers: Born between 1965 and 1983

Boomers: Born between 1946 and 1964

Elders: Born between 1945 or earlier

Practicing Christian: Those who attend a religious service at least once a month, who say their faith is very important in their lives and self-identify as a Christian.

Evangelicals: meet nine specific theological criteria. They say they have made “a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in their life today,” that their faith is very important in their life today; believe that when they die they will go to Heaven because they have confessed their sins and accepted Jesus Christ as their Savior; strongly believe they have a personal responsibility to share their religious beliefs about Christ with non-Christians; firmly believe that Satan exists; strongly believe that eternal salvation is possible only through grace, not works; strong agree that Jesus Christ lived a sinless life on earth; strong assert that the Bible is accurate in all the principles it teaches; and describing God as the all-knowing, all-powerful, perfect deity who created the universe and still rules it today. Being classified as an evangelical is not dependent on church attendance, the denominational affiliation of the church attended or self-identification. Respondents were not asked to describe themselves as “evangelical.”

Love Jesus but Not the Church: Those who self-identify as Christian and who strongly agree that their religious faith is very important in their life, but are “dechurched” (have attended church in the past, but haven’t done so in the last six months or more).

Spiritual but Not Religious #1: Those who self-identify as spiritual but say their faith is not very important in their lives.

Spiritual but Not Religious #2: Those who self-identify as spiritual but do not claim any faith (atheist, agnostic or unaffiliated).

About Barna

Barna research is a private, non-partisan, for-profit organization under the umbrella of the Issachar Companies. Located in Ventura, California, Barna Group has been conducting and analyzing primary research to understand cultural trends related to values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors since 1984.

© Barna Group, 2017