From Barna Group, 2017

We live in an increasingly secular American culture. In this new age, religion is in retreat from the public square, and traditional institutions like the church are no longer functioning with the cultural authority they once held in generations past. Today, nearly half of America is unchurched. But even though more and more Americans are abandoning the institutional church and its defined boundary markers of religious identity, many still believe in God and practice faith outside its walls.

This is the first of a two-part exploration of faith and spirituality outside the church. Let’s start with a look at the fascinating segment of the American population who, as the saying goes, “love Jesus but not the church.”

Traditionally Christian—with Exceptions

To get at a sense of enduring faithfulness among Christians despite a rejection of the institutional church, Barna created a metric to capture those who most neatly fit this description. It includes those who self-identify as Christian and who strongly agree that their religious faith is very important in their life, but are “dechurched”—that is, they have attended church in the past, but haven’t done so in the last six months (or more). These individuals have a sincere faith (89% have made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important to their life today), but are notably absent from church.

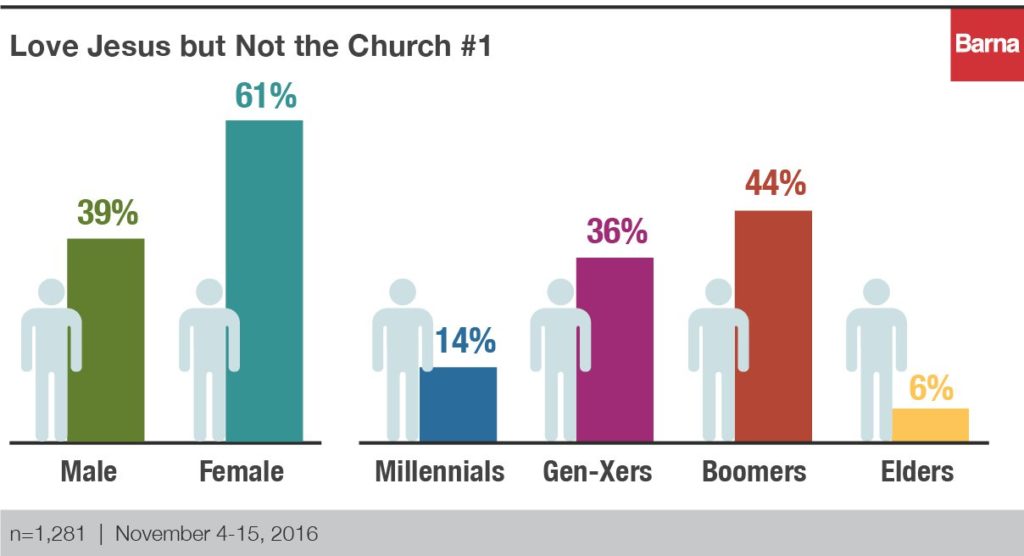

According to aggregate Barna tracking data, this group makes up one-tenth of the population, and it’s growing (up from 7% in 2004). The majority are women (61%), and four-fifths (80%) are between the ages of 33 and 70. That is, they are mostly Gen-Xers (36%) and Boomers (44%), not Millennials (14%) or Elders (6%). Though Millennials are the least churched generation, they are also the least likely to either identify as Christian or say faith is very important to their life, explaining their underrepresentation among this group. Elders are underrepresented for the opposite reason—they are the generation most likely to attend church regularly.

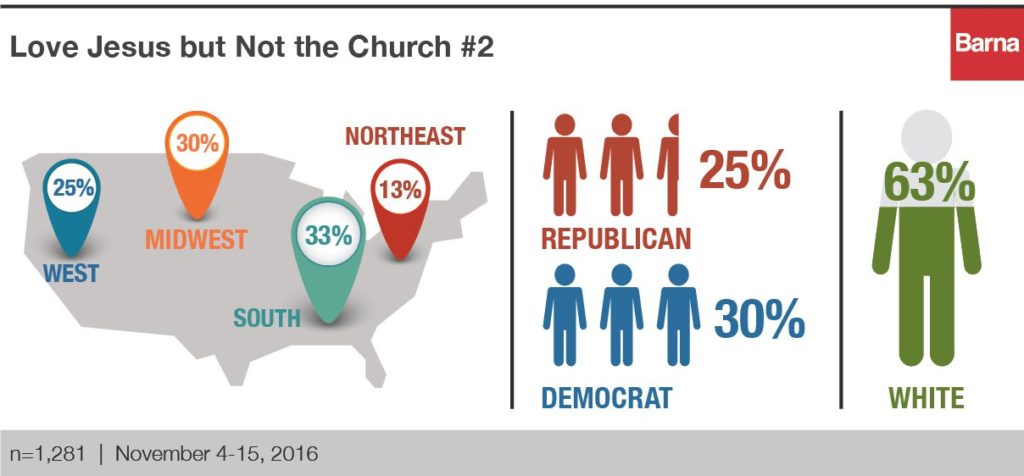

This group also appears to be mostly white (63%) and concentrated in the South (33%), Midwest (30%) and West (25%), with very few hailing from the Northeast (13%)—a region typically home to the most post-Christian cities in America. The fact that they are just as likely to identify as Democrat (30%) than Republican (25%) is interesting, particularly for Christians and those in the South and Midwest, who typically are disproportionately Republican. It’s possible that left-leaning people of faith are encountering some level of political discord with their church, which may have prompted an exit.

Orthodox Belief Despite Church Absence

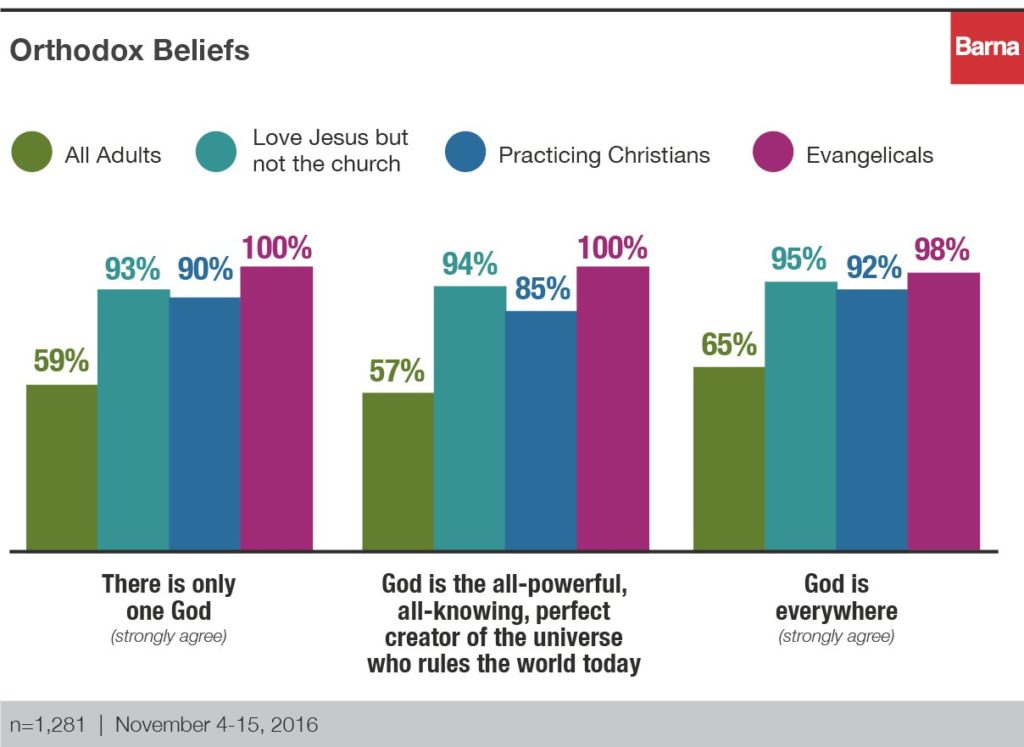

Despite leaving the church, this group has maintained a robustly orthodox view of God. In every case, their beliefs about God are more orthodox than the general population, even rivaling their church-going counterparts. For instance, they strongly believe there is only one God (93% compared to U.S. adults: 59% and practicing Christians: 90%); affirm that “God is the all-powerful, all- knowing, perfect creator of the universe who rules the world today” (94% compared to U.S. adults: 57% and practicing Christians: 85%); and strongly agree that God is everywhere (95% compared to U.S. adults: 65% and practicing Christians: 92%).

Positive, if Amorphous, Views of Religion

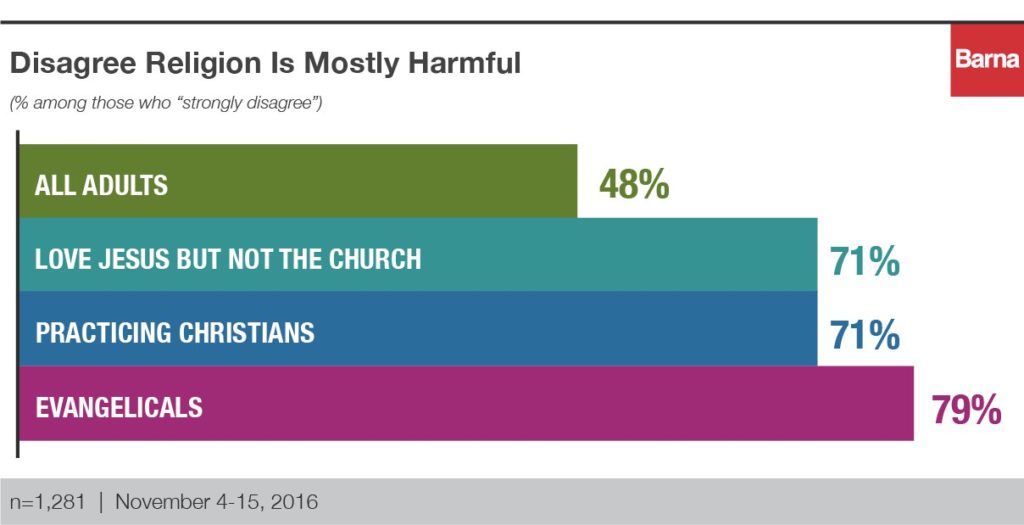

Despite their apparent discomfort with the church, this group still maintains a very positive view of religion. When asked whether they believe religion is mostly harmful, their response once again stood out from the general population, and aligned with their church-going counterparts (71% strongly disagree, compared to 71% among practicing Christians and 48% among U.S adults).

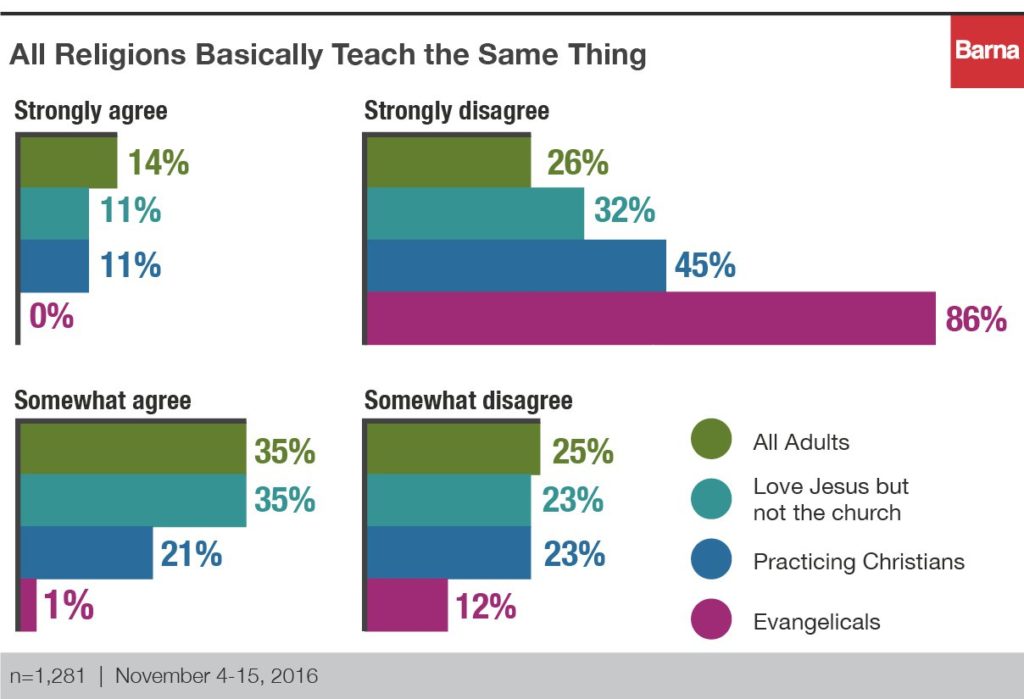

But the story changes slightly when it comes to the distinctiveness of Christianity: Just over half (55%) disagree (strongly and somewhat) that all religions basically teach the same thing, much closer to the general population (51%) than practicing Christians (68%), and even further from evangelicals (86%). In the absence of a rigid religious identity provided by the authority of the church, this group appears to be more affirming of the claims of other religions and open to finding and identifying common ground.

Privately Spiritual

Due to their enduring religious affiliation and overtly religious faith, this group falls outside of the characterization of “spiritual but not religious” folks—the topic of next week’s article. But one thing they do share is a sense of spirituality. Slightly fewer than nine in 10 (89%) identify as “spiritual,” on par with practicing Christians (90%), and far exceeding the national average (65%).

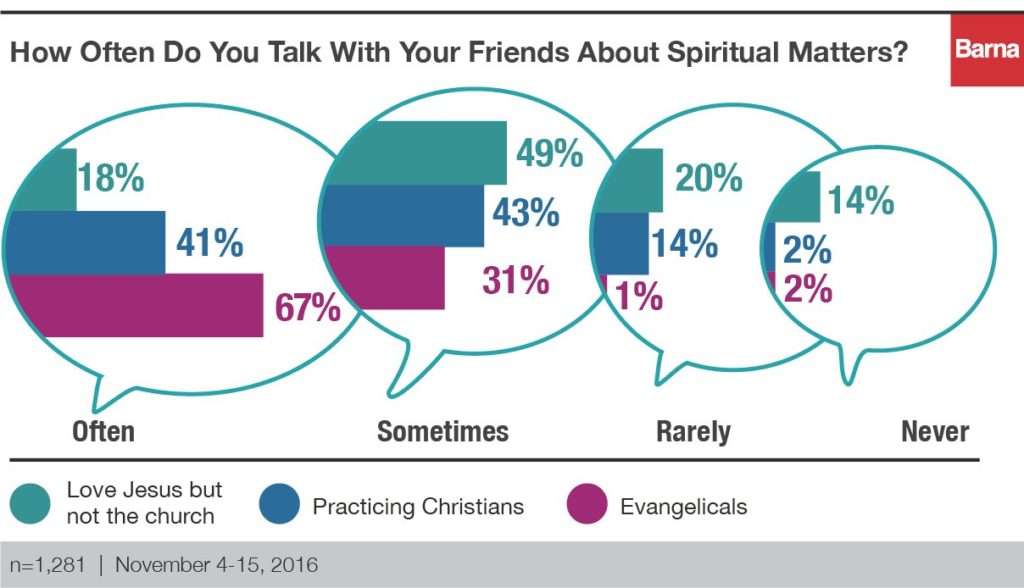

But unlike practicing Christians and evangelicals, this spirituality is deeply personal—even private—with many preferring to keep spiritual matters to themselves: only two in five (18%) say they talk with their friends about spiritual matters often. This is less than half as much as practicing Christians (41%), and almost four times less than evangelicals (67%), who are known for evangelizing and sharing their faith. When asked specifically about evangelizing—whether they personally have a responsibility to tell others about their religious beliefs—the differences are even more striking. Fewer than three in 10 of the “love Jesus but not the church” group agrees strongly that they have a responsibility to proselytize (28%), compared to more than half of practicing Christians (56%) and all of Evangelicals (100%). So, while “spiritual” topics may often or sometimes come up, the actual act of trying to convert someone is a low priority for this group.

Informal Paths to God

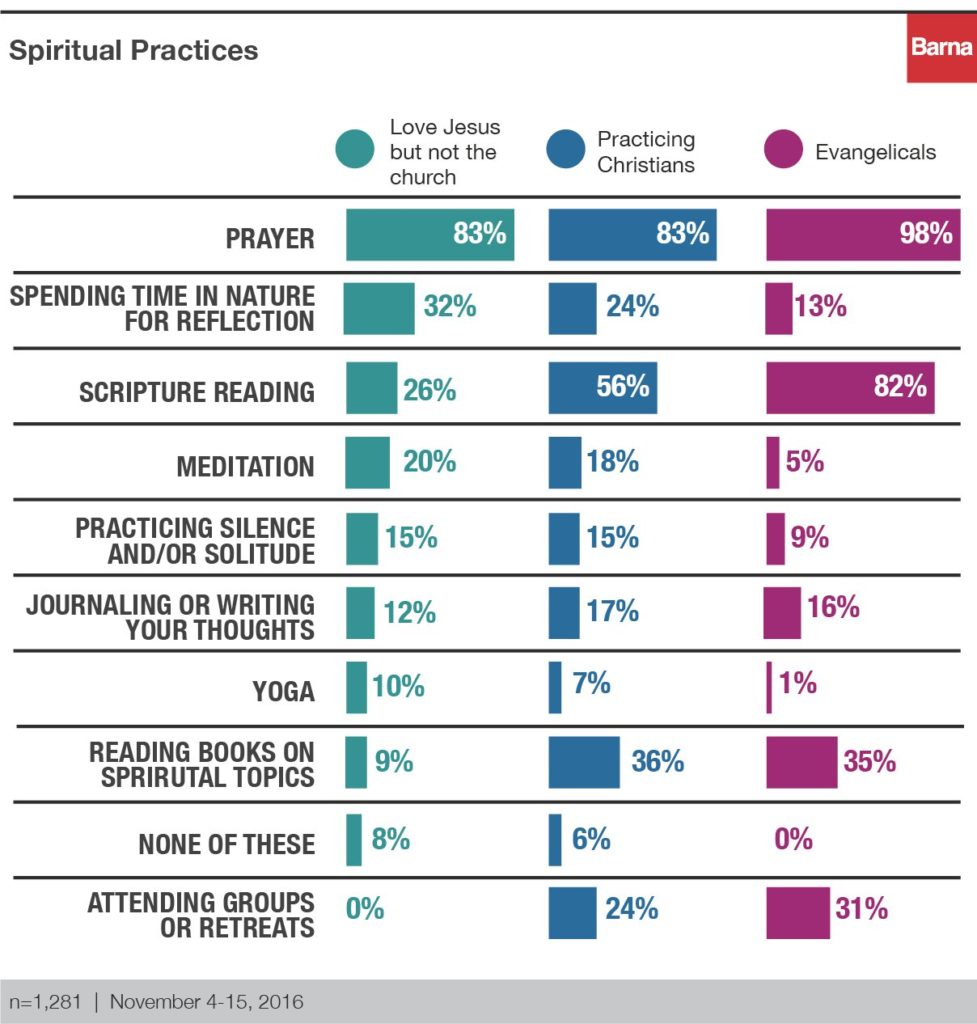

This group still actively practices their faith, albeit in less traditional ways. They maintain an active prayer life (83%, compared to 83% of practicing Christians), but only read scripture half as much as the average practicing Christian (26% compared to 56%). In addition, they are much less likely to read a book on spiritual topics (9% compared to 36% of practicing Christians), and never attend groups or retreats (compared to 24% of practicing Christians). This all points to a broader abandonment of authoritative sources of religious identity, leading to much more informal and personally-driven faith practices. They are certainly still finding and experiencing God, but they are more likely to do so in nature (32% compared to 24% of practicing Christians), and through practices like meditation (20% compared to 18%), yoga (10% compared to 7%) and silence and solitude (both 15%).

What the Research Means

We will explore this topic of faith outside the church much more in the coming weeks, but one thing that’s most worth noting among this group of people who “love Jesus but not the church” is their continued commitment to faith. “This group represents an important and growing avenue of ministry for churches,” says Roxanne Stone, editor in chief of Barna Group. “Particularly if you live in a more churched area of the country, it’s more than likely you have a significant number of these disaffected Christians in your neighborhoods. They still love Jesus, still believe in Scripture and most of the tenets of their Christian faith. But they have lost faith in the church. While many people in this group may be suffering from church wounds, we also know from past research that Christians who do not attend church say it’s primarily not out of wounding, but because they can find God elsewhere or that church is not personally relevant to them. The critical message that churches need to offer this group is a reason for churches to exist at all. What is it that the church can offer their faith that they can’t get on their own? Churches need to be able to say to these people—and to answer for themselves—that there is a unique way you can find God only in church. And that faith does not survive or thrive in solitude.”

About Barna

Barna research is a private, non-partisan, for-profit organization under the umbrella of the Issachar Companies. Located in Ventura, California, Barna Group has been conducting and analyzing primary research to understand cultural trends related to values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors since 1984.